Goddard and his rocket – March 1926

Today is Goddard Day. On March 16, 1926, scientist Robert Goddard successfully launched the first liquid-fueled rocket.

In 1915, he had challenged accepted beliefs about propulsion when he theorized that a rocket could produce thrust in the vacuum of space, where there was no air to push against. He was widely ignored and paid for the supplies he needed to build his prototypes from his salary as a part-time teacher at Clark University in his hometown of Worcester, MA.

By 1916, the costs of his research exceeded his ability to pay and he applied to several places for financial support. Only the Smithsonian Institution granted Goddard $5,000 after he sent them a paper he’d written, “A Method for Reaching Extreme Altitudes.”

In 1920, the Smithsonian published the article, which included a thought experiment about sending a rocket carrying flash powder to the surface of the moon, where it would ignite and be visible through telescopes on Earth. Although it amounted to eight lines on the next to last of 69 pages, the press pounced upon it, ridiculing Goddard as a fool.

The most notable mockery came from the New York Times, which ran an editorial the day after the paper’s release, which read, in part:

…after the rocket quits our air and and really starts on its longer journey, its flight would be neither accelerated nor maintained by the explosion of the charges it then might have left. To claim that it would be is to deny a fundamental law of dynamics, and only Dr. Einstein and his chosen dozen, so few and fit, are licensed to do that.

That Professor Goddard, with his “chair” in Clark College and the countenancing of the Smithsonian Institution, does not know the relation of action to reaction, and of the need to have something better than a vacuum against which to react–to say that would be absurd. Of course he only seems to lack the knowledge ladled out daily in high schools.

The author and, by extension, the Times, showed a failure of imagination and fact-checking. Goddard, a physics professor, had read Newton’s Principia Mathematica in high school and recognized that his Third Law could allow for the navigation of objects through space. A rocket ejecting fuel while traveling at high speed creates its own action and equal, opposite reaction, enabling thrust in a vacuum.

Goddard’s response to the ridicule heaped upon him was simple and straightforward:

Every vision is a joke until the first man accomplishes it. Once realized, it becomes commonplace.

Six years later, Goddard launched the first rocket fueled by gasoline and liquid oxygen from his Aunt Effie’s farm in Auburn, MA. His log entry the next day described the scene:

Even though the release was pulled, the rocket did not rise at first, but the flame came out, and there was a steady roar. After a number of seconds it rose, slowly until it cleared the frame, and then at express train speed, curving over to the left, and striking the ice and snow, still going at a rapid rate.

The rocket, later named “Nell,” rose just 41 feet during a 2.5-second flight that ended 184 feet away in a cabbage patch but it was an important demonstration that liquid propellants were possible. Goddard paved the way for a generation of scientists to make space exploration a reality.

In 1930, Goddard received a grant from the Guggenheim Foundation and relocated to Roswell, NM, with his wife and a small team to continue his research in seclusion. Within a few years, his rockets had broken the sound barrier, reaching speeds up to 741 miles per hour and heights of up to 1.7 miles. (The speed of sound isn’t static. It’s influenced by altitude and temperature. So even though 741 mph is too slow to break the sound barrier at sea level, it’s more than enough when you launch from an elevation high above sea level—like New Mexico—and climb upward from there.)

Goddard paved the way for the Space Age but died in 1945 at age 62, before he could witness its fruition. Now known as the father of modern rocketry, he is recognized for his research and its role as a precursor to the field of rocket propulsion.

In 1951, Goddard’s widow and the Guggenheim Foundation jointly filed a patent infringement claim against the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) and the Department of Defense. In June of 1960, the U.S. government paid the estate $1 million to acquire the rights to more than 200 patents covering “basic inventions in the field of rockets, guided missiles, and space exploration.” NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, MD, is named in his honor.

The original launch site was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1966 with a stone marker on what is now the Pakachoag Golf Course in Auburn, MA.

On July 17, 1969, the day after Apollo 11 launched on its way to the moon, the New York Times issued a correction to its 1920 editorial:

Further investigation and experimentation have confirmed the findings of Isaac Newton in the 17th Century and it is now definitely established that a rocket can function in a vacuum as well as in an atmosphere. The Times regrets the error.

It made no mention of Robert Goddard.

![]()

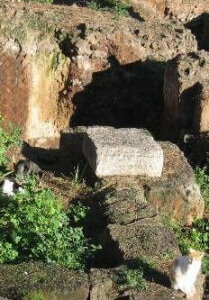

Today is Ear Muff Day, celebrating the date in 1877 when Chester Greenwood was awarded a patent for his “ear-mufflers.” Before long, his hometown of Farmington, Maine became the Earmuff Capital of the World, producing up to 50,000 pairs of Greenwood Champion Ear Protectors each year.

Today is Ear Muff Day, celebrating the date in 1877 when Chester Greenwood was awarded a patent for his “ear-mufflers.” Before long, his hometown of Farmington, Maine became the Earmuff Capital of the World, producing up to 50,000 pairs of Greenwood Champion Ear Protectors each year.