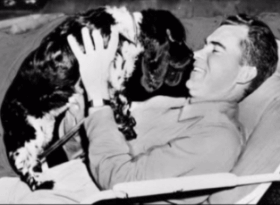

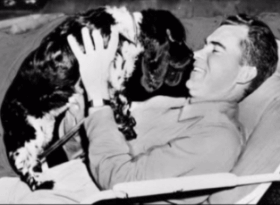

Checkers with Nixon

Today is Checkers Day, also known as National Dogs in Politics Day. On September 23, 1952, Senator Richard M. Nixon addressed the nation to dispute allegations he had taken $18,000 from a secret campaign slush fund. His speech became known as the Checkers Speech because of his reference to the family dog.

General Dwight D. Eisenhower was running for president with Nixon on the ticket for vice president. Angry citizens protesting Nixon’s perceived financial impropriety appeared on the campaign trail, causing Eisenhower to question the wisdom of keeping Nixon as his running mate.

On September 20, Republican National Committee (RNC) official Bob Humphreys suggested Nixon appear on the television interview program Meet the Press. Nixon’s campaign manager Murray Chotiner rejected that idea and insisted upon complete control of the broadcast “without interruption by possibly unfriendly press questions.”

The RNC raised $75,000 to buy 30 minutes of prime time while Eisenhower’s staff secured sixty NBC stations to air the speech, with radio coverage by CBS. It was scheduled for September 23, 1952, at 6:30 Pacific Time, after Texaco Star Theater, starring Milton Berle.

On September 21, New York Governor Thomas Dewey called Nixon to tell him that most Eisenhower aides wanted him off the ticket. He suggested Nixon end his speech by asking the public to write and express their opinions. Dewey added that if the response was not strongly in his favor, he should withdraw.

Late that evening, Eisenhower called and told Nixon he was reluctant to drop him and thought he should be allowed to make his case before the American people. When Nixon asked him to make a decision about the ticket immediately after the broadcast, Eisenhower declined. Nixon responded, “General, there comes a time in matters like this when you’ve either got to s**t or get off the pot.” Eisenhower replied that it could take three to four days to gauge the public’s reaction.

On September 23, two hours prior to the speech, Governor Dewey called to say that Eisenhower’s aides had unanimously called for Nixon’s resignation and he was to announce his withdrawal at the end of his speech. When Nixon asked what the general had said, Dewey stated he hadn’t talked to him directly but that the direction came from such close aides that it must reflect Eisenhower’s wishes.

Nixon complained that it was very late for him to change his remarks but Dewey said there was no need as he could add his resignation at the end of his speech. Dewey went on to suggest he also announce his resignation from the Senate so the public could vindicate him by voting him back in the special election that would follow.

The senator was quiet for so long that Dewey was obliged to break the silence by asking what he planned to do. Nixon told him he didn’t know and if Eisenhower’s aides wanted to find out, they could watch just like everyone else. At 6:30 pm, they certainly did, along with millions of other viewers.

As Nixon spoke to the audience from his seat behind a desk, producers occasionally cut away to show his wife Pat watching raptly from an armchair onset. She later said that she looked so attentive because she was wondering what he would say.

He proceeded to pose skeptical questions of himself and then respond as if to the media, without fear of follow-up inquiry. He talked about his family’s income and debts, their mortgaged homes in Washington, D.C. and California, his $4,000 life insurance policy, loans from his parents and their two-year-old Oldsmobile.

He summed up: “Well, that’s about it. That’s what we have and that’s what we owe. It isn’t very much but Pat and I have the satisfaction that every dime that we’ve got is honestly ours.” He then, seemingly spontaneously, addressed accusations Pat wore fur coats bought with fund money. “I should say this—that Pat doesn’t have a mink coat. But she does have a respectable Republican cloth coat. And I always tell her that she’d look good in anything.”

What he said next deserves a place among the most inspired bits of political stagecraft in history. He began, “One other thing I should probably tell you, because if I don’t, they will probably be saying this about me, too. We did get something, a gift, after the election.”

“A man down in Texas heard Pat on the radio mention that our two youngsters would like to have a dog, and, believe it or not, the day we left before this campaign trip we got a message from Union Station in Baltimore, saying they had a package for us. We went down to get it. You know what it was?

“It was a little cocker spaniel dog, in a crate that he had sent all the way from Texas, black and white, spotted, and our little girl Tricia, the six-year-old, named it Checkers. And you know, the kids, like all kids, loved the dog, and I just want to say this, right now, that regardless of what they say about it, we are going to keep it.”

With that statement, Nixon endeared himself to voters. Here was a man so honest that he offered up every detail of his financial position, so persecuted he felt the need to confess the one gift he’d accepted—an adorable puppy!—and so dedicated to his family that he’d risk political suicide to keep it.

He didn’t announce his resignation from the campaign. He told viewers, “Let me say this: I don’t believe that I ought to quit because I am not a quitter.” He urged them to make the call. “Wire and write the Republican National Committee whether you think I should stay on or whether I should get off. And whatever their decision, I will abide by it.”

The response was overwhelmingly pro-Nixon. Eisenhower didn’t seem to mind keeping him on the ticket. Less than two months later, they won the election. Twenty years later, President Nixon, elected in 1969, was accused of using campaign money to fund illegal activities and then cover them up.

On August 9, 1974, facing impeachment and possible prosecution, he became the first and only president to quit. Vice President Gerald Ford succeeded Nixon. One of his first acts as president was to pardon him of any and all crimes he committed while in office.

Checkers died in 1964. He is buried at the Bide-A-Wee Pet Cemetery in Wantagh, New York. Nixon died thirty years later at age 81 and is buried on the ground of the Nixon Library and Museum in Yorba Linda, California.

Happy Checkers Day!

Related holidays:

National Veep Day

Pardon Day

Today is Presidential Debate Day. It commemorates the first televised debate, which aired on September 26, 1960, and changed the way American citizens select their leaders.

Today is Presidential Debate Day. It commemorates the first televised debate, which aired on September 26, 1960, and changed the way American citizens select their leaders.