National Handcuff Day

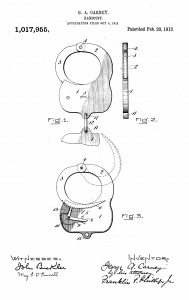

Today is National Handcuff Day. On February 20, 1912, George A. Carney was awarded U.S. patent number 1,017,955 for his “swinging bow ratchet-type” adjustable handcuff.

Today is National Handcuff Day. On February 20, 1912, George A. Carney was awarded U.S. patent number 1,017,955 for his “swinging bow ratchet-type” adjustable handcuff.

Prior to Carney’s invention, there was no standard style and handcuffs were heavy and awkward to use. His lightweight design features a freely swinging arm that enables law enforcement officers to secure cuffs on a suspect quickly and easily, with one hand. More than 100 years later, most handcuffs still use the same swing-through structure, with some minor modifications.

James Milton Gill purchased the patent, founded the Peerless Handcuff Company, and in 1914 began to sell the first model based on Carney’s configuration. The company has been innovating and improving cuff design ever since. In 1932, Peerless introduced the barrel-style key which quickly became the universal standard for all handcuffs.

National Handcuff Day was created in 2010 to honor Carney’s invention. Each year, Peerless and Handcuff Warehouse: The Ultimate Source for Restraints sponsor a contest in which the prize is a free set of cuffs. In 2016, they awarded a pair to the entrant who most closely guessed the weight of this pile. Give it a whirl then read on to find the answer.

source: National Handcuff Day

If you guessed 49.5, it’s a shame you didn’t enter. You’d have won a shiny new pair of handcuffs. (Sheri Barber took the prize with her guess of 49.)

The contest has since returned to its usual quiz format. Click here to enter this year’s competition. (You could use the internet to help answer the questions. Only you, your flexible ethical standards and your Google search history will know for sure.) Please note that we cannot control any ads you may see or email lists you may be added to as a result of your actions.

Have a happy National Handcuff Day!

![]()

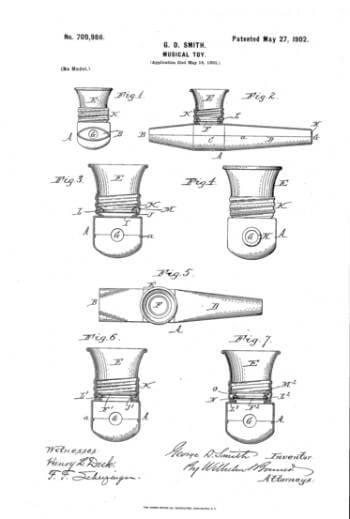

vanced musical training is required, a player has the potential to become a virtuoso almost immediately. That fact may also be what keeps the kazoo from getting the respect it deserves.

vanced musical training is required, a player has the potential to become a virtuoso almost immediately. That fact may also be what keeps the kazoo from getting the respect it deserves.