February 15 is Susan B. Anthony Day

Today is Susan B. Anthony Day. Susan Brownell Anthony, born February 15, 1820, was an American abolitionist and feminist who fought for women’s rights, including the right to vote, until her death in 1906.

Today is Susan B. Anthony Day. Susan Brownell Anthony, born February 15, 1820, was an American abolitionist and feminist who fought for women’s rights, including the right to vote, until her death in 1906.

The only weird thing about this holiday is that it is officially observed in only five states: Wisconsin, Florida, West Virginia, New York, and California.

Anthony’s father believed his daughters should get a good education and sent her away to study. When she returned at age 14—when women weren’t allowed to attend college—she took one of the few jobs deemed acceptable: teaching. She earned $2.50 a week while her male counterparts earned $10.00. She felt equal work deserved equal pay.

At that time, married women were required to give their wages to their husbands. Wives were property, as were their children. Any inheritance a wife received automatically belonged to her husband as well. Only single women could enter into contracts. Women, regardless of marital status, were not allowed to vote on social and political issues that affected their lives.

In 1840, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott, two women who would later become Anthony’s compatriots, were turned away and not allowed to speak against slavery at the World Anti-Slavery Convention in London—because they were women.

In 1848, Mott, Stanton, and others held a historic meeting in Seneca Falls, NY, where they issued a Declaration of Sentiments and Resolutions, detailing the disenfranchisement of women. It’s widely believed that Anthony met Stanton and Mott there.

In fact, she was not introduced to the two women until 1851. According to Lisa Tetrault, author of The Myth of Seneca Falls: Memory and the Women’s Suffrage Movement, 1848-1898, this misperception was encouraged by Anthony and Stanton to depict a unified movement, with the 1840 incident leading directly to the Seneca Falls “watershed moment” for the cause of women’s equality.

In actuality, there were many divisive issues. Some wanted to prioritize African-American male suffrage above white women’s suffrage. Splinter groups formed in support of free love, tax resistance, temperance, and social purity. Many African-American women participated while also fighting to improve working conditions for freedwomen.

There’s no arguing that Susan B. Anthony was an essential part of the movement. She traveled around the country, rallying women with her rousing speeches. She was known to say, “The Constitution says, ‘We the people,’ not, ‘We the male citizens.'”

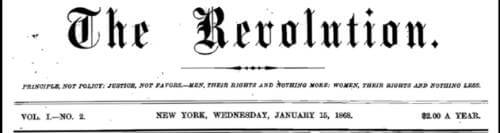

In January 1868, she and Stanton launched a weekly newspaper, The Revolution, in New York City. It focused primarily on women’s rights and suffrage, but also covered topics such as politics, finance, and the labor movement. Its motto was “Principle, not Policy—Men, their rights and nothing more: Women, their rights and nothing less.”

The Fifteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution was ratified on February 3, 1870. It states, “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.”

Although it made no mention of women, Anthony decided to vote in the 1872 presidential election, arguing that she qualified as a “citizen” and was protected by the amendment. She and a group of other women were arrested after voting in her hometown of Rochester, NY. A trial was scheduled for early the following year.

Prior to 1878, federal courts barred criminal defendants from testifying or addressing the jury in their own trials. Before the trial, however, they were allowed to attempt to “educate” anyone who might be selected as a juror.

According to the Federal Judicial Center, “Anthony spoke in twenty-nine villages and towns of Monroe County, asking ‘Is It a Crime for a U.S. Citizen to Vote?’ When she delivered her lecture in Rochester, the county seat, a daily newspaper printed her speech in full, circulating it further.

In May, after many delays, U.S. Attorney Richard Crowley successfully petitioned to have the trial moved to a neighboring county, negating Anthony’s efforts to persuade the jury pool. She immediately drew up a schedule to visit every town she could in the month before her trial on June 17, 1783.

A jury of twelve men and Justice Ward Hunt listened to Crowley’s prosecutorial arguments for the better part of the day. Anthony’s defense attorney Henry Selden presented his case during the latter part of the afternoon.

The following day was devoted to Crowley’s recitation of the government’s case. At the end of the day, Justice Hunt declared that Anthony had knowingly violated the law and that, as a result, there was nothing for the jury to determine; it must return a verdict of guilty.

Selden argued for the jury’s right to decide guilt or innocence and its need to determine Anthony’s intent when voting. Hunt again told the jury it must deliver a guilty verdict, and the clerk refused to allow Selden to poll the jury.

Selden returned to court the next day to file a motion for a new trial. In circuit courts, a motion was heard by the same judge whose actions had caused an attorney to file that motion. In other words, Justice Hunt would be asked to decide whether he had violated the Constitution by denying Anthony a trial by jury.

Unsurprisingly, Hunt denied the motion, stating that the right to a trial by jury “exists only in respect of a disputed fact,” and no facts were in dispute. Before sentencing her, Hunt asked Anthony if she had anything to say.

She responded with perhaps the most impassioned speech in the history of the fight for women’s rights, offering a blistering indictment of everything from the trial to male sovereignty to the responsibility to disobey unjust laws, such as those that had made it illegal to give a cup of water to a fleeing slave. (Transcript here.)

She condemned the proceedings she said “trampled under foot every vital principle of our government.” She had not received justice under “forms of law all made by men,” “failing, even, to get a trial by a jury not of my peers.”

Sentenced to pay a $100 fine and the costs of the prosecution, she swore to “never pay a dollar of your unjust penalty.” In a move calculated to preclude an appeal to a higher court, Hunt ended the trial by announcing, “Madam, the Court will not order you committed until the fine is paid.”

She continued to agitate, traveling to almost every state, speaking publicly at each stop. It’s been estimated that, in 60 years of tireless effort to win women the right to vote, she gave 75 to 100 speeches per year. She served as president of the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) from 1892 to 1900 and continued to fight until her death on March 13, 1906, at the age of 86.

The Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution was ratified on August 18, 1920. It states, “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex.”

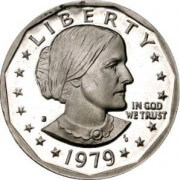

In 1979, the U.S. Mint introduced the Susan B. Anthony dollar, the first coin to bear the likeness of an American woman. We think she would have found it funny to be enshrined on federal money…

…since she never paid that fine.

![]()