December 10 is Dewey Decimal Day

Today is Dewey Decimal Day. Melville Louis Kossuth Dewey was born on December 10, 1851, in the hardscrabble town of Adams Center in Northern New York State. At the age of 22, while studying at Amherst College in Boston, he devised one of the most efficient methods of classification ever known, copyrighting the Dewey Decimal System three years later in 1876. He’s proven to be much harder to classify.

Today is Dewey Decimal Day. Melville Louis Kossuth Dewey was born on December 10, 1851, in the hardscrabble town of Adams Center in Northern New York State. At the age of 22, while studying at Amherst College in Boston, he devised one of the most efficient methods of classification ever known, copyrighting the Dewey Decimal System three years later in 1876. He’s proven to be much harder to classify.

Dewey abhorred waste, championing conversion to metric measurements and the use of streamlined phonetic spellings. Upon leaving home, he shortened his name to Melvil and attempted to change his last name as well, but admitted defeat when his bank refused to recognize his new signature. Otherwise, we’d be referring to the Dui Decimal System right now.

Many libraries at that time utilized a numbering system that indicated the floor, aisle, section and shelf upon which each book was stored. When rearrangement became necessary, all of the books had to be reclassified. Dewey was determined to devise a simple, workable, permanent classification system.

He formulated a system of Arabic numerals with decimals for book classification. All printed knowledge would be organized into ten numerical classifications ranging from 000 to 900, with as many decimals as necessary to define the content of the book being classified.

Within three years, A Classification and Subject Index For Cataloguing and Arranging the Books and Pamphlets of a Library was published. It was widely adopted in the United States and England as well as elsewhere in the world. This system has proven to be enormously influential and remains in widespread use.

In 1883, Dewey was recruited by Columbia University to become its librarian. The following year, he founded the School of Library Economy—the first school for librarians ever organized. It opened on January 5, 1887. He personally enrolled each student. Of the twenty-six, nineteen were women.

Columbia forbade admittance to females. Since Dewey believed that women were destined to become librarians, he ignored this rule. That didn’t make him a feminist, though. His enrollment questionnaire required an applicant to report her height, weight, hair and eye color. Inclusion of a photograph was strongly recommended.

In spite of the school’s financial success, Columbia shuttered it the following year and Dewey moved on, accepting an invitation to become director of the New York State Library in 1883. In 1895, he founded a private resort in Lake Placid, New York, and began to campaign for the Olympic Games to be held there. Ten years later, Dewey was forced to resign as State Librarian after complaints that his Lake Placid Club denied entrance to smokers, drinkers, blacks and Jews.

In 1926, he moved to Florida to establish a new branch of the resort. He died on December 26, 1931, in Lake Placid, Florida. The following year, Lake Placid, New York, hosted the Winter Olympics.

Turns out Dewey was more complicated than his system.

![]()

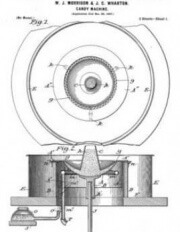

Dentist William Morrison and confectioner John C. Wharton invented the first electric spinning

Dentist William Morrison and confectioner John C. Wharton invented the first electric spinning  In 1949, Gold Medal Products launched a

In 1949, Gold Medal Products launched a  Although that’s a laudable goal, most of us have outgrown the sanitized version of events we learned in school. Can we celebrate the beauty of an idea while acknowledging the ugliness beneath the surface? It’s a complex subject, worthy of impassioned debate. For our purposes, however, let’s lighten the mood and debunk a few myths about Christopher Columbus.

Although that’s a laudable goal, most of us have outgrown the sanitized version of events we learned in school. Can we celebrate the beauty of an idea while acknowledging the ugliness beneath the surface? It’s a complex subject, worthy of impassioned debate. For our purposes, however, let’s lighten the mood and debunk a few myths about Christopher Columbus.