Forefathers’ Day

Forefathers’ Day commemorates the landing of the Mayflower and the pilgrims’ subsequent founding of Plymouth Colony in North America. The ship arrived on December 11, 1620. So why is the anniversary celebrated on December 21 or December 22?

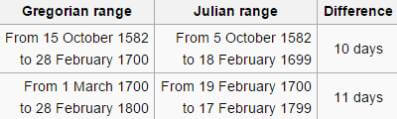

In 1582, Pope Gregory XIII announced his Gregorian calendar would replace the Julian calendar introduced in 46 B.C. by Julius Caesar. The Roman emperor’s system had miscalculated the length of the solar year by 11 minutes.

This concerned the pope because it meant that Easter, traditionally observed on March 21, fell further away from the spring equinox with each passing year. Ten days were subtracted to realign the seasons with the calendar. The beginning of the new year was also moved to January 1 from March 25.

England and the colonies didn’t convert to the new system until September 1752, causing the month’s calendar to look like this:

cal 9 1752 September 1752 S M Tu W Th F S 1 2 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30

Benjamin Franklin wrote of the change, “It is pleasant for an old man to be able to go to bed on September 2, and not have to get up until September 14.”

When the Old Colony Club of Plymouth inaugurated Forefathers’ Day in 1769, it mistakenly reset the anniversary of the ship’s landing to December 22. (Perhaps it utilized the 11-day difference appropriate to its own century.)

Members still observe the holiday on December 22, wearing top hats and marching down Plymouth’s main street led by a drummer. After firing a small cannon at the end of the route, they return to their club for breakfast and toasts to the Pilgrims.

Other groups like the General Society of Mayflower Descendants observe the occasion, sometimes called Compact Day, on December 21, as does the Pilgrim Society, a group formed in 1820 that serves a traditional dinner of succotash, stew, corn, turnips, and beans.

No matter how or when you choose to celebrate it, have a happy Forefathers’ Day!

![]()

Today is Bake Cookies Day. So, you know, preheat the oven. Here’s a tried-and-true formula from

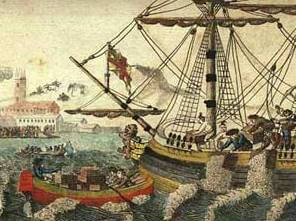

Today is Bake Cookies Day. So, you know, preheat the oven. Here’s a tried-and-true formula from  Today is the anniversary of the Boston Tea Party. On December 16, 1773, the Sons of Liberty, disguised as Mohawks, stole aboard three British ships and emptied 342 chests of tea into Boston Harbor. This act of defiance, part of a wave of resistance throughout the colonies, was a protest against British rule. Earlier that year, Parliament had passed the

Today is the anniversary of the Boston Tea Party. On December 16, 1773, the Sons of Liberty, disguised as Mohawks, stole aboard three British ships and emptied 342 chests of tea into Boston Harbor. This act of defiance, part of a wave of resistance throughout the colonies, was a protest against British rule. Earlier that year, Parliament had passed the